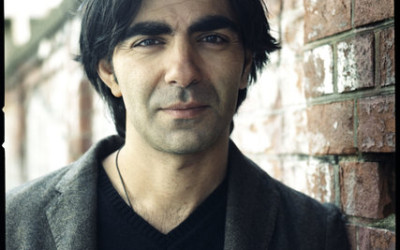

The director Fatih Akin, 41, born in Germany to Turkish parents, has mined his mixed heritage to make two complex, critically acclaimed films թ§Չ-Չթ§Չ-ժHead-Onթ§Չ-Թ (2004) and թ§Չ-ժThe Edge of Heavenթ§Չ-Թ (2007) թ§Չ-Չ which comprise the first parts of what he calls his թ§Չ-ժLove, Death and the Devilթ§Չ-Թ trilogy. The final installment, թ§Չ-ժThe Cut,թ§Չ-Թ which is set to open at the Venice Film Festival on Sunday, goes back in time to 1915 to replay scenes from one of the most painful and contentious chapters in Turkish history: the Armenian genocide.

The film stars the French-Algerian actor Tahar Rahim (թ§Չ-ժA Prophetթ§Չ-Թ) as an Armenian blacksmith who travels around the world թ§Չ-Չ from Aleppo to Havana to North Dakota թ§Չ-Չ in search of his two daughters, with whom he lost touch after the outbreak of systematic violence that would eventually claim the lives of an estimated 1.5 million Armenians.

թ§Չ-ժThe Cutթ§Չ-Թ թ§Չ-Չ shot on 35-millimeter film with Cinemascope lenses, with locations in five countries and a budget of 15 million euros, or about $20 million թ§Չ-Չ is by far the most ambitious film Mr. Akin has ever attempted, and he admits to being a bit jittery about its reception. The film was previously expected to debut at the Cannes Film Festival, but Mr. Akin pulled it from consideration for թ§Չ-ժpersonal reasons.թ§Չ-Թ In the following edited interview, he discusses why he brought թ§Չ-ժThe Cutթ§Չ-Թ to Venice, how he thinks the film will be received in Turkey, and the wide range of directors who influenced it, including Elia Kazan and Terrence Malick.

Q. You recently told a newspaper in Turkey that the country was ripe for a major film that dealt with the Armenian genocide. The paper has since received death threats. Have you changed your mind?

A. No, I still believe Turkey is ready. Two friends of mine, both producers, read the script. One of them said they will throw stones, the other said they will throw flowers. Thatթ§Չ-Չ§s what it is թ§Չ-Չ guns and roses. But Iթ§Չ-Չ§ve shown the film to people who deny the fact that 1915 was a genocide and to people who accept it and both groups had the same emotional impact. I hope the film could be seen as a bridge. For sure there are radical groups, fascist groups, who fear any kind of reconciliation. And the smaller they are, the louder they bark. The newspaper that I gave the interview to, Agos, is actually an Armenian-Turkish weekly newspaper where the journalist Hrant Dink worked.

Q. He was Armenian and was murdered in 2007 by a teenage Turkish nationalist. In 2010, you attempted to make a film about Dinkթ§Չ-Չ§s life, but couldnթ§Չ-Չ§t find an actor in Turkey to play the part.

A. I wrote down five names of Turkish actors I thought could play him. And all of them were nervous about the script. I donթ§Չ-Չ§t want to hurt anybody, I donթ§Չ-Չ§t live in Turkey, in a way I am safe, protected. But these actors, maybe theyթ§Չ-Չ§d have some problems. No film is worth that.

Q. The scenes from թ§Չ-ժThe Cutթ§Չ-Թ that are set in Turkey were actually filmed in Jordan. Why?

A. Mostly because of logistical reasons. The film takes place in 1915, in southeastern Turkey, very close to todayթ§Չ-Չ§s Syria, actually. And I needed a lot of old trains, historical trains, like the ones from the Baghdad Railway that Germans were building through the Turkish Empire in those days. You find those trains and those landscapes in Jordan.

Q. But you also filmed parts of թ§Չ-ժThe Cutթ§Չ-Թ in Germany, Cuba, Canada, Malta.

A. Itթ§Չ-Չ§s a road movie. The plot is about a father looking for his lost children. The Armenian genocide wasnթ§Չ-Չ§t only about violence, it was also about forced migration, the spreading around the world of these people, from Anatolia to Port Said, Egypt; to Havana; to Canada; to California; to Hong Kong.

Q. To what extent was this story based on the life of a real person?

A. I did a lot of research while I was writing this and I discovered diaries of Armenians who went to Havana in their early 20s. Oral histories and literature about the death camps and the death marches. I collected a lot of very rich portraits of witnesses and tried to sew them together.

Q. Youթ§Չ-Չ§ve described the film as a kind of western.

A. Yes. թ§Չ-ժThe Cutթ§Չ-Թ is not just a film about the material, itթ§Չ-Չ§s about my personal journey through cinema, and the directors who I admire and who influence my work. Elia Kazanթ§Չ-Չ§s թ§Չ-ժAmerica Americaթ§Չ-Թ is a very important influence. So is the work of Sergio Leone, how he used framing. Itթ§Չ-Չ§s also an homage somehow to Scorsese. I wrote this film with Mardik Martin, Martin Scorseseթ§Չ-Չ§s very early scriptwriter who wrote թ§Չ-ժMean Streetsթ§Չ-Թ and the first draft of թ§Չ-ժRaging Bull.թ§Չ-Թ Because he was Armenian, I discovered him on this project, and he helped me write it. And we spoke a lot about obsessional characters in Scorsese films.

The film deals also a lot with my admiration for Bertolucci, and Italian westerns and how Eastwood adapted Italian westerns. And the way we try to catch the light, always having it behind us, is very inspired by the work of Terrence Malick. So this film is very much in the Atlantic ocean, somewhere near the Azores թ§Չ-Չ for a European film itթ§Չ-Չ§s too American, for an American film itթ§Չ-Չ§s too European.

Q. Why do the Turkish characters in your film speak Turkish while the Armenians speak English?

A. The main reason is that if I wanted to control the film, I had to control the dialogue. And I donթ§Չ-Չ§t speak Armenian at all. There are a lot of examples in the history of cinema. Bertolucci shot թ§Չ-ժThe Last Emperorթ§Չ-Թ with the Chinese speaking English. I used the concept that Polanski used in թ§Չ-ժThe Pianist,թ§Չ-Թ where he made all the Polish characters speak English and the Germans speak German, making English a language of identification. Itթ§Չ-Չ§s a clear concept, but itթ§Չ-Չ§s surprising for some people because theyթ§Չ-Չ§re used to my films in German and Turkish. But this film is more about the whole world. Itթ§Չ-Չ§s not set in a minimalistic frame.

Q. How was working with Tahar Rahim?

A. թ§Չ-ժA Prophetթ§Չ-Թ made a huge impact on me, it was great film թ§Չ-Չ a masterpiece. And 90 percent of the quality of the film came from Tahar Rahim. When we met, there were a lot of things that we shared. We had relevant backgrounds թ§Չ-Չ he had grown up in France with an Arab background, and I had grown up in Germany with a Turkish background.

Q. Are you excited or nervous about the debut of your film at Venice?

A. Iթ§Չ-Չ§m nervous and excited. I spent too much time on it թ§Չ-Չ usually you spend two years with a film, but on this film I spent seven years, the last four years I was working every day. Yes, Iթ§Չ-Չ§m nervous.

Q. թ§Չ-ժThe Cutթ§Չ-Թ was initially headed to the Cannes Film Festival but you pulled the movie at the last minute, citing թ§Չ-ժpersonal reasons.թ§Չ-Թ What happened?

A. We showed the film to Cannes and Venice at the same time. The reaction of Venice was very enthusiastic and Cannes was a bit much more careful, like they always are. So I was nervous, and I followed my instincts. But I couldnթ§Չ-Չ§t talk about my decision in the press because Venice asked me to wait until they made their own announcement. The people in Cannes never rejected the film but I had the feeling that it wasnթ§Չ-Չ§t what they expected from me. Because itթ§Չ-Չ§s historical, because itթ§Չ-Չ§s in English, itթ§Չ-Չ§s not minimalistic, Iթ§Չ-Չ§m not sure. But I cannot fulfill other peopleթ§Չ-Չ§s expectations. I have to fulfill my own.

Be the first to comment